It is worth asking if the landscape, as a genre that deals with the representation of the place – whether natural or urban, real or imagined – consists of an imitation of reality as it is perceived, or if it is merely a cultural elaboration. While, oriented to the production of visual culture, gender and product could be considered as a representation of the environment mediated by the mental structure that produces it. This is evidenced by his being subject to transformations of style derived from geographical origin, history or the values and ideas that operate between the model and the artist.

And, in this sense, it seems that landscape is a genre that adapts to transformations of style and aesthetic changes with surprising ease, to the point that one might consider whether its adaptability is evidence and even a catalyst vehicle for these transformations.

The landscape, in our culture, becomes relevant with the rise of Renaissance humanism, and with the progressive consolidation of an individualistic worldview derived from the growing strength of the bourgeoisie. Thus, both the contributions of the Flemish primitives (for example, Patinir in El Paso de la Estigia, ca. 1520) and those of the Italian artists of the Quattrocento are notable for its development. Not surprisingly, according to Pseudo-Manetti, it was through an urban landscape – a representation of the Florence Duomo Baptistery – that Brunelleschi created the first pictorial work through geometric perspective with a vanishing point. Fully humanistic, it thus granted, to the eye of the artist and the viewer, the role of being the central point that orders the world according to rational and harmonious principles. Indeed, this small urban landscape was, without a doubt, a work as innovative as it was revolutionary, whose purpose found in the landscape the most suitable genre to advance painting in terms of representing space.

The genre experienced a golden age in the 17th century, during which two trends were consolidated. On the one hand, the Dutch landscape provides artists such as Jacob Van Ruisdael, a painter endowed with an exceptional sensitivity for the representation of cloudscapes, clouds and light effects in the sky. Likewise, with regard to the representation of urban landscapes, two preserved works by Vermeer within this genre are valuable.

On the other hand, the brilliant classicist contributions of Claude Lorrain stand out in his landscapes with a soft melancholic atmosphere, or of Poussin, who develops a genre that combines figure, architecture and landscape, based on erudition, balance and the application of classicist values. In any case, this school conveys a friendly and orderly concept of nature.

As for the 18th century, on the one hand, the contributions of the English school of landscape artists stand out, with excellent figures such as Gainsborough and John Cozens, whose magnificent landscapes already announce the feeling of the sublime typical of Romanticism. On the other hand, the magnificent urban landscapes of the Venetian school, rich in nuances of atmosphere and color, among which those of Canaletto and Guardi stand out.

It seems, then, that the landscape is linked to the innovation and transformation of painting, efficiently and effectively permeating innovation and the revolutionary, since, lacking narrative content, the artist can surrender more freely to lyricism and plasticity. . It is not surprising that the 19th century elevated landscape to the category of a fundamental genre, unleashing important innovations in concept, technique and transformation of the genre.

Romanticism looks at nature to discover not only what could be harmonious and orderly about it, but to find in it a catalyst for emotions and a scene of spectacular, ungovernable and threatening forces, of sublime masses. Thus, for example, the impressive clouds and light effects and atmosphere of Turner, a true master of color and lyricism. Or the magnificent landscapes of Friedrich, not exempt from symbolic and pantheistic readings, subject, already in his time, to controversy for his innovative treatment of the genre. Indeed, the contribution of both artists expands the landscape, giving it greater plastic, lyrical and symbolic depth. And the landscape, in turn, proves to be an optimal medium to host these achievements. Nineteenth-century culture promotes a landscape at the forefront of nature, either through an increasing direct contact with nature – as advocated by Daubigny, Rousseau and other Barbizon painters – or through the investigation of impressionism – with titans like Monet, Sisley or Pisarro – who turn to the landscape to develop an innovative painting and technique, based on the direct imitation of the perception of light in nature through color.

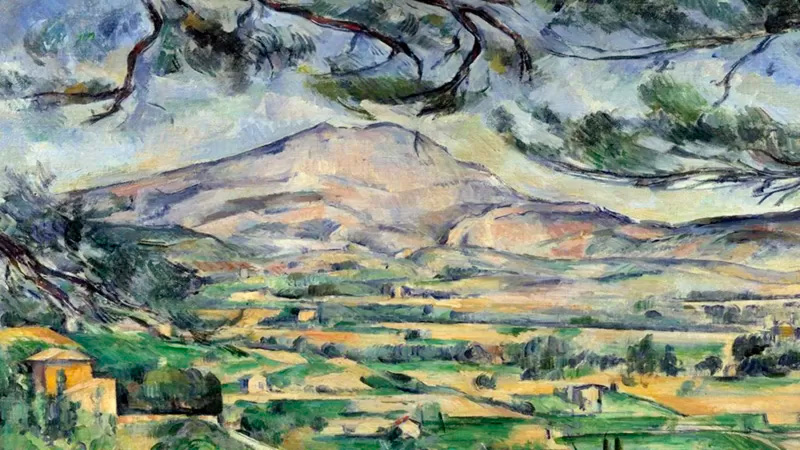

But the achievements of the century do not end here, but rather the post-impressionist landscape, influenced by the end-of-the-century Japanese trend – the case of the Nabis – should be considered as a primitivism that prefigures – with Gauguin and Van Gogh – the attitude of the first avant-gardes . This magnificent cycle is closed by the work of Cézanne as a landscape artist, whose special technique and classicist sense of painting opens the doors to the cubist discipline.

The first years of the 20th century are also proof that the landscape adapts favorably to most of the contributions of the avant-garde. It is worth considering the innovative use of color by the Fauves – with excellent landscapes signed by Matisse or Friesz – at the same time that expressionists such as Nolde or Kirchner revisit the romantic sensibility to give it a greater lyrical intensity not exempt from primitivism. In the same way, the metaphysical urban landscapes of Chirico, clearly imaginary, but full of classical references in architecture and statuary and endowed with a subtle air of strangeness and melancholy, or the surrealist landscapes of Delvaux or Dali, disturbing, bleak and suggestive… All these renovating tendencies that have a full place in the landscape, show the way in which the genre has contributed to its development, placing itself, in some cases, at the forefront of the most innovative painting. But its value is not estimated only in its adaptability or in its ability to renew the plastic, but rather it is a genre that provides enormous surprises and satisfaction to those who enjoy painting.

David Luquero